Peggy Derrick

Native Americans have served in the U.S. Armed Forces since the American Revolution, even though they were not granted citizenship and the right to vote until 1924, with the Indian Citizenship Act. As many as 25,000 saw active duty in World War II.

Five of those who served were the Littlejohn brothers from Brownsville, Minnesota, members of the Ho-Chunk Nation.

Four of the Littlejohns — Edward, Warren, Lawrence and Howard — joined the U.S. Army, while Woodrow joined the Army Air Corps. Three served in the South Pacific, and two in Africa and Europe, and one, Howard, was killed at the Battle of the Bulge. The other four survived to return home to the poverty and prejudice they had grown up with.

At the time of their enlistment, newspapers featured them in articles that said things like “heap big trouble is in store for the Axis.” Even in the act of recognizing the Littlejohns, white society parodied them with stereotypes and tried to diminish their sacrifice.

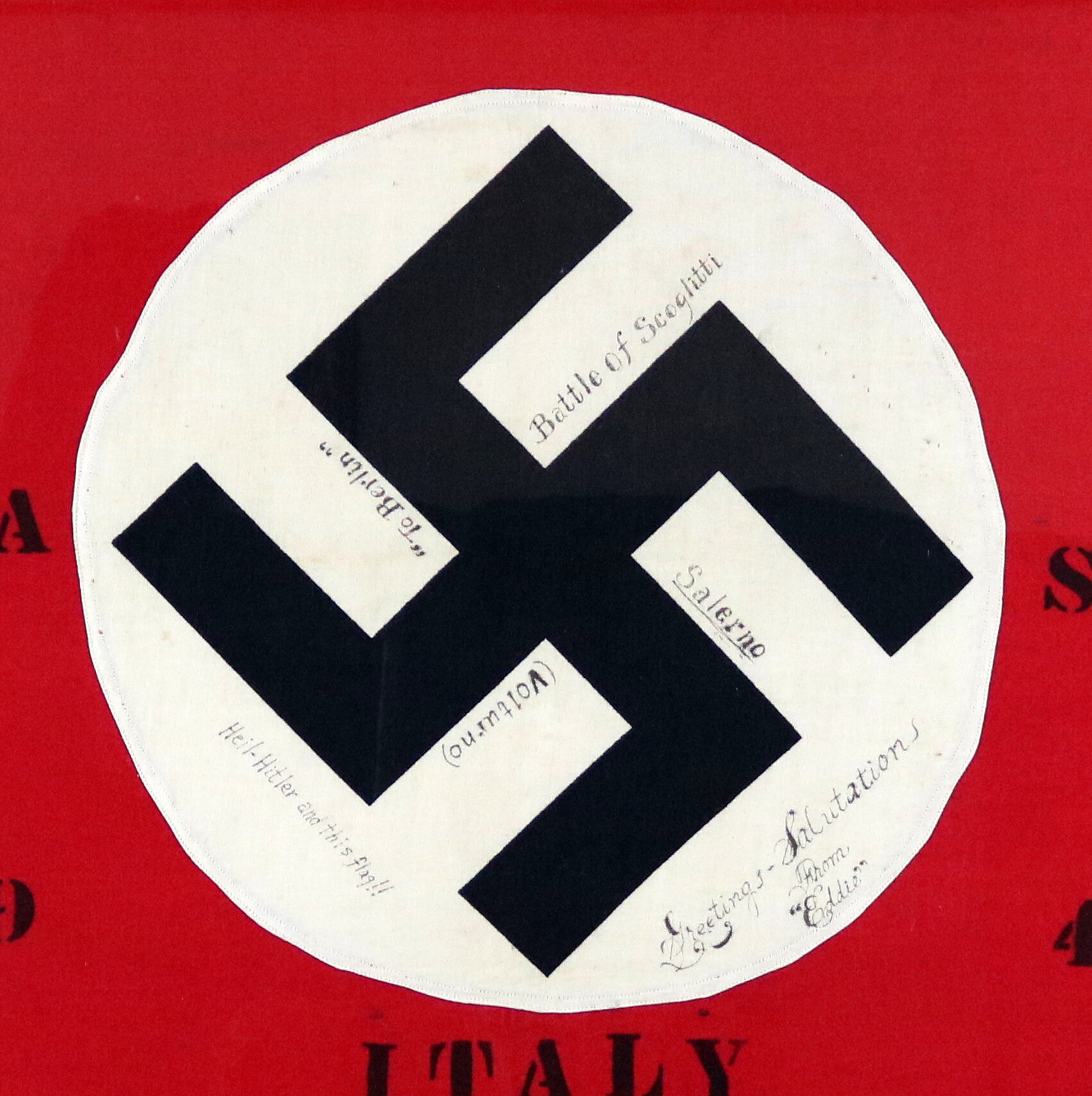

Eddie Littlejohn was certainly proud of his exploits, and he chose to memorialize them on this Nazi flag he brought home as a souvenir. Littlejohn served under General George Patton, as a combat engineer, in North Africa, Sicily and Italy.

The flag is large, 56” by 37.” The black swastika is screen printed onto the white wool circle, which is sewn onto the red wool background.

The appliqued white circle has irregular edges and looks homemade, which raises the possibility that it was sent home first, and later sewn back on to a red wool background.

This theory is supported by one of the handwritten inscriptions on the white circle: “Greetings-Salutations, from Eddie.”

This flag is especially significant because of the way in which Littlejohn has taken the Nazi symbol and co-opted it to make it a record of his own exploits as a soldier. The standard symbolism of a manufactured item is here merely the backdrop for the story of the individual who claimed it.

Littlejohn has painted and stenciled on the history of his service over the surface of the flag. It reads in large stenciled black letters on the red ground: Invasion of Axis Europe; Africa, Sicily, Italy; 1943; Eddie G. Littlejohn.

Also on the white background around the central swastika he has written with very fine penmanship the names of individual battles and places where he had served: Salerno (the site of the Allied Forces landing in Italy on Sept. 3, 1943), Volturno (site of the German defensive line), and the Battle of Scoglitti (site of the Allied invasion of Sicily). And there are a young man’s cocky nose-thumbing: to Berlin, and Heil Hitler and his flag.

Flags are representative group symbols that have been around as long as there have been textiles.

The practice of taking trophies in battle probably goes back even longer, and this flag was certainly Littlejohn’s trophy. It is what textile historians call a “user-modified” object: the original meaning of the flag has been subsumed in the meaning given to it by one Native American soldier. It is this personal story, overlaid on top of the backdrop of the Nazi symbol that makes this such an interesting artifact.

Unlike nearly every other artifact described in Things That Matter, this flag does not belong to the La Crosse County Historical Society: It is on loan to us from Eliot, the son of the Eddie Littlejohn. Eliot himself is a veteran, having served in the Vietnam War, and he takes pride in the legacy of his father and his uncles.

Eliot Littlejohn left the flag with us in the hopes of seeing a small display about his father’s military service.

LCHS does not presently have a public gallery space to put up such a display. However, we dream of someday having an exhibit that would tell stories of local Native American veterans, for there are many Ho-Chunk veterans.

An artifact like this giant swastika needs to be displayed and interpreted with thoughtful, sensitive context.

There is nothing innately “cool” about Nazi paraphernalia, and the world is sadly full of such items. As an authentic WWII artifact, it is important; but as an artifact that documents the experience of a young Ho-Chunk soldier from the Coulee Region, it is an irreplaceable treasure.

This article was originally published in the La Crosse Tribune on November 9, 2019.