Peggy Derrick

Catalog Number: 2015.014.036

It has been approximately 40 years since Hmong people began to relocate from refugee camps in Thailand to La Crosse. In the aftermath of the Vietnam War thousands of Hmong were forced to flee Laos, and spent many years in the camps. There they recreated their village life as best they could, continuing traditional ways of living, including the production of fabric and decorative needlework called Paj ntaub, or flower cloth. Skilled craftswomen, using little more than needle, scissors and thread, created intricate masterpieces of embroidery and reverse applique to decorate clothing with traditional abstract designs.

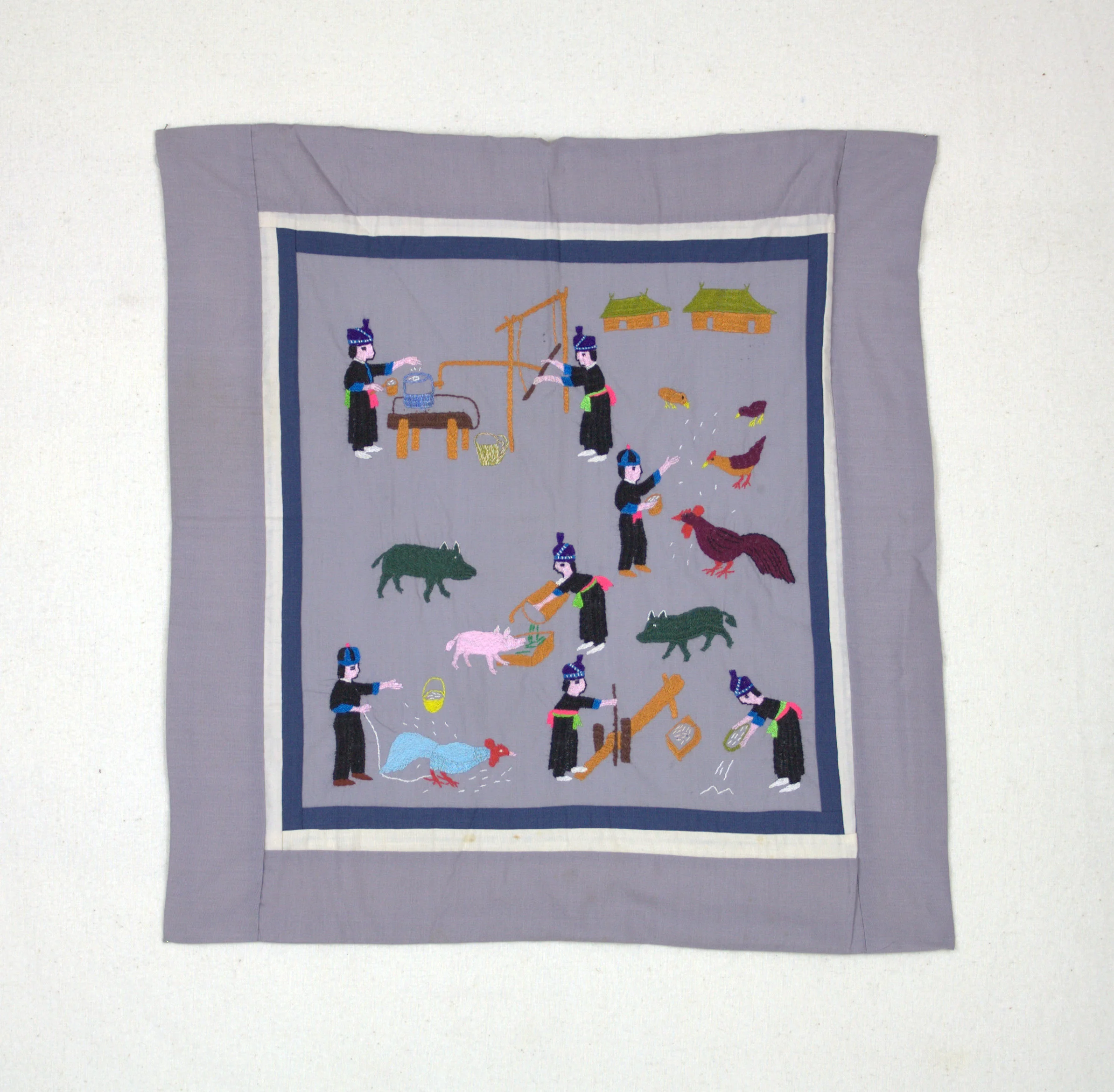

Yet here in North America the most immediately recognizable Hmong needlework is something quite different: these are the “story cloths,” filled with recognizable imagery of people and animals, often engaged in activities that are part of a narrative, or story. The stories are filled with scenes of traditional Hmong village life and dangerous escapes from soldiers chasing them through the jungle and across the Mekong River to safety in Thailand. Some include the next chapter in their lives, a journey by airplane to the U.S.A. and life in a strange new place with more cars than animals, potatoes instead of rice, and English instead of the Hmong language. And where a market economy replaced traditional village economy.

It turns out that these story cloths are a part of that process of learning to survive in their new environment. New styles of Paj ntaub were developed to be sold to tourists in Thailand and to Americans in the U.S. No one knows exactly who made the first narrative story cloth, but it is often said that it was a man who first drew the figures on a cloth for women to embroider, and it is true that it became a man’s job, while women did the actual embroidery. The soft blue or grey backgrounds are said to have been chosen to appeal to Western tastes.

Apparently both the colors and the stories have been very appealing because these story cloths became extremely popular. They were made both in the camps and in the United States for sale on the market. They vary in size from very small—this one is 15” by 16.5,” to several feet in both dimensions. They can include hundreds of small figures engaged in activities ranging from feeding chickens and pigs, to hunting tigers, to crossing the Mekong on rafts, to flying in jumbo jets.

This little story cloth belonged to Betty Weeth, a resident of La Crosse who worked with social agencies to facilitate the resettlement process for the first Hmong people to make La Crosse their new home. It is easy to imagine that it was made by a person feeling homesick, with imagery restricted to domestic activities the new residents must have missed from their homeland: feeding livestock, processing their rice crop by hand, and weaving at an upright loom.

The story cloth is an object caught in a moment in history: it filled a need at a specific time in the history of the Hmong people, but as younger generations assimilate, fewer women will engage in needlework. Story cloths may cease to be made, or they may tell different stories as the story of the Hmong people unfolds.

This article was originally published in the La Crosse Tribune on June 4th, 2016.

This object can be viewed in our online collections database by clicking here.