Ivy King

Catalog Number: 2015.021.01

The first African American to win a medal in the modern Olympics came from La Crosse. George Coleman Poage completed this feat on Aug. 31, 1904. While his legacy was largely forgotten, La Crosse has recently started to recognize this man and his accomplishments.

Copyright La Crosse County Historical Society

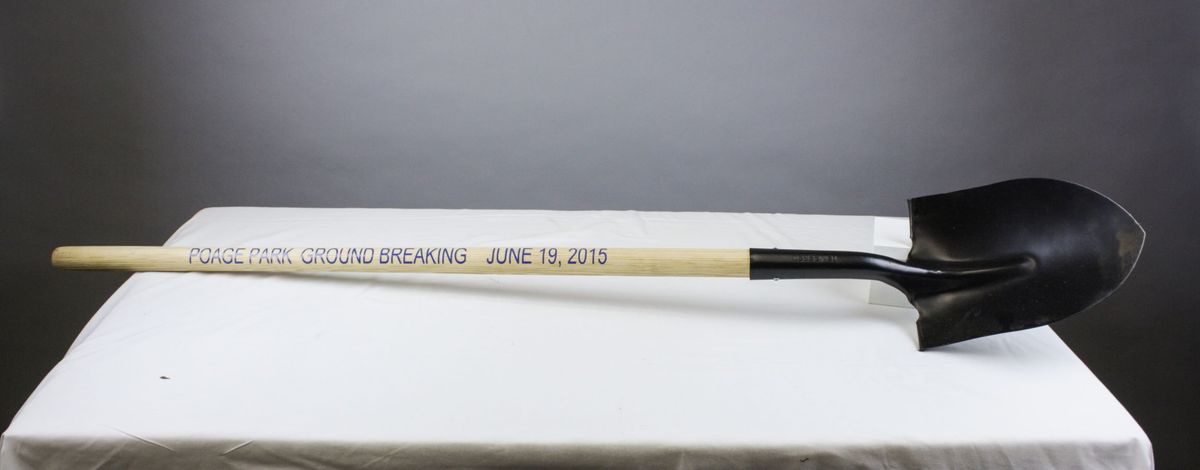

This shovel commemorates the renaming of Hood Park to Poage Park, which is a step in recognizing and remembering this nearly forgotten history.

Poage was born in 1880 in Hannibal, Mo., but he moved to La Crosse at the age of 4. It was here he began his academic and athletic careers. He and his sister were among the first African Americans to attend La Crosse High School, which later became Central High School. Poage also was one of the most accomplished athletes during his education. His preferred sport was track, and he frequently won many of the races.

After high school, Poage continued his education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he was the first African American on the track team. Similar to his high school career, Poage won countless competitions.

In 1904, Poage participated in the Olympic Games at St. Louis. The games correlated with the World’s Fair, and these were the first Olympics held in the U.S. Unfortunately, these games had heavy racial segregation, and many African Americans boycotted the fair and the Olympics, but not Poage. He competed in four events and won bronze medals in the 200-meter and the 400-meter low hurdles.

After competing in the Olympics, Poage taught and coached high school students in St. Louis for 10 years. He then purchased a plot of land in Minnesota and farmed until relocating to Chicago. In Chicago, Poage worked for the U.S. Postal Service until his retirement, and he remained there until his death in 1962.

For many years, Poage and his accomplishments were ignored and nearly forgotten by the La Crosse community, but in recent years the community has begun to recognize Poage. The Poage Park Commemorative Shovel was used on June 19, 2015, at the groundbreaking ceremony in renaming Hood Park. The park was renamed to George C. Poage Park in order to honor his memory and his many achievements.

This article was originally published in the La Crosse Tribune on June 10, 2017.

This object can be viewed in our online collections database by clicking here.